Eclipse: Halfway Between an Electric Car and the Formula 1

The ÉTS Eclipse student club was founded 25 years ago, in 1992, when the idea of electric cars was still just a dream. The objective of the project is to design and manufacture an ultra-efficient, solar-powered race car. Its complexity lies in achieving balance between sustainability and component performance.

The international solar car academic competitions in which Eclipse participates are extremely demanding in every aspect: intense heat, torrential rains and bumpy roads are inevitable occurrences at these events. Some will say that this is what makes the project more interesting, while others find it is what really brings these competitions closer to actual market applications.

From Electric Car…

Indeed, solar car design is virtually identical to that of electric cars sold on the market today. In a nutshell, this type of transport can be described as a giant battery on wheels. Furthermore, circuits that control the device can be added: battery management system (BMS), engine controllers and driver interface. So far, this description could be applied as much to the Eclipse as to the Tesla Model S. What is more, the two cars are powered by the same type of lithium-ion batteries, which implies the presence of the same type of both active and passive safety systems. The difference between the Eclipse and electric cars available on the market is the recharging method: the Eclipse is powered by solar panels while the Tesla is recharged at a terminal connected to the electrical distribution network.

…To Race Car!

On the mechanical side, the design philosophy of a solar car is closer to that of a Formula 1. The F1 industry, where everything is dictated by the need to exhilarate spectators, relies primarily on car performance. All parts are therefore manufactured from ultra-light, resistant and rigid materials so that the car can convert all the engine power into lightning speeds. Although the Eclipse performance objectives are quite different, the means used to achieve them are very similar.

F1 cars are lightweight to improve acceleration. Because their efficiency is generally greater when speeds are constant, the energy consumption of solar cars is multiplied by 4 or 5 during acceleration. A simple look at Newton’s second law (F = ma) leads to the conclusion that decreasing the mass, through the use of better materials, will have a significant impact on the racing car’s performance.

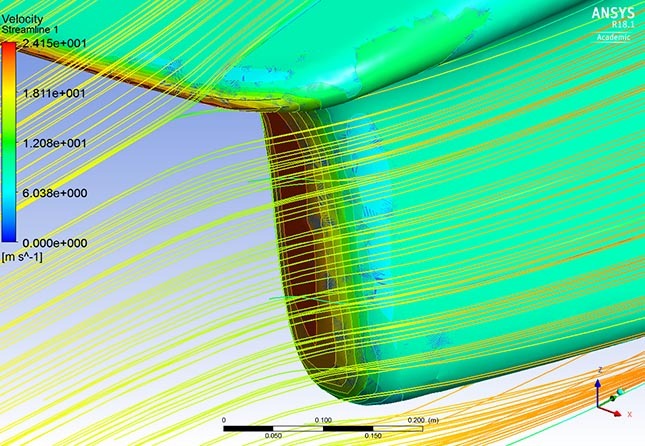

Finite element analysis during the development of the latest prototype

In the Formula 1 arena, the cars’ aerodynamic properties are maximized to improve traction without adding a single gram of weight. Aerodynamic properties are at the same level, but with diametrically opposed objectives in the design of solar cars. Indeed, the profile design must ensure that the prototype can run at high speeds without being slowed down by drag forces. In the case of a Formula 1, the drag force effect creates a downward vector (negative lift or downforce). Lift on a solar car that runs at high speeds creates not only a force vector opposite to vehicle movement but also an additional load on the bearing systems, which leads to increased friction and therefore a double decrease in efficiency!

It is interesting to see that there is now a branch of motor racing, Formula E, which links all these technological concepts, including battery management, in a high-speed performance event.